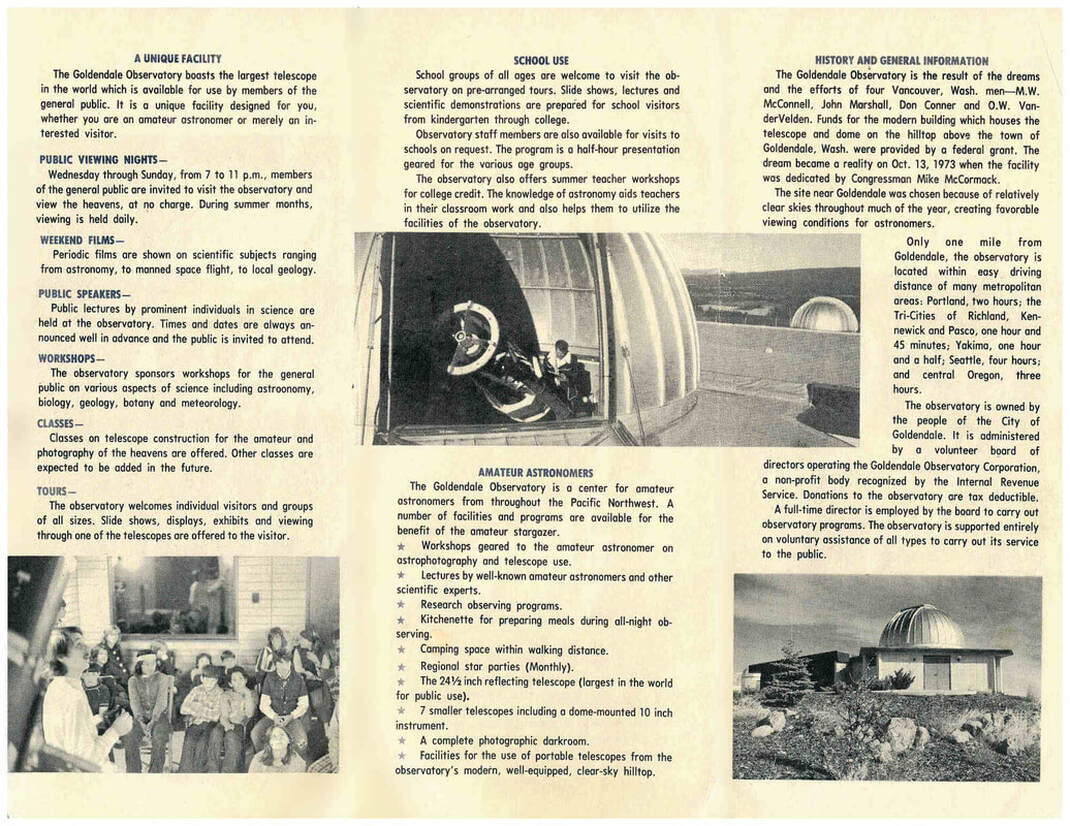

With its telescope originally built by amateur astronomers for Clark College in Vancouver, Washington, and set on a hill just 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the center of Goldendale, this Washington State Park Heritage Site has attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors since its dedication in 1973. Goldendale was chosen in order to place the telescope where it would have a night sky unhampered by light pollution.

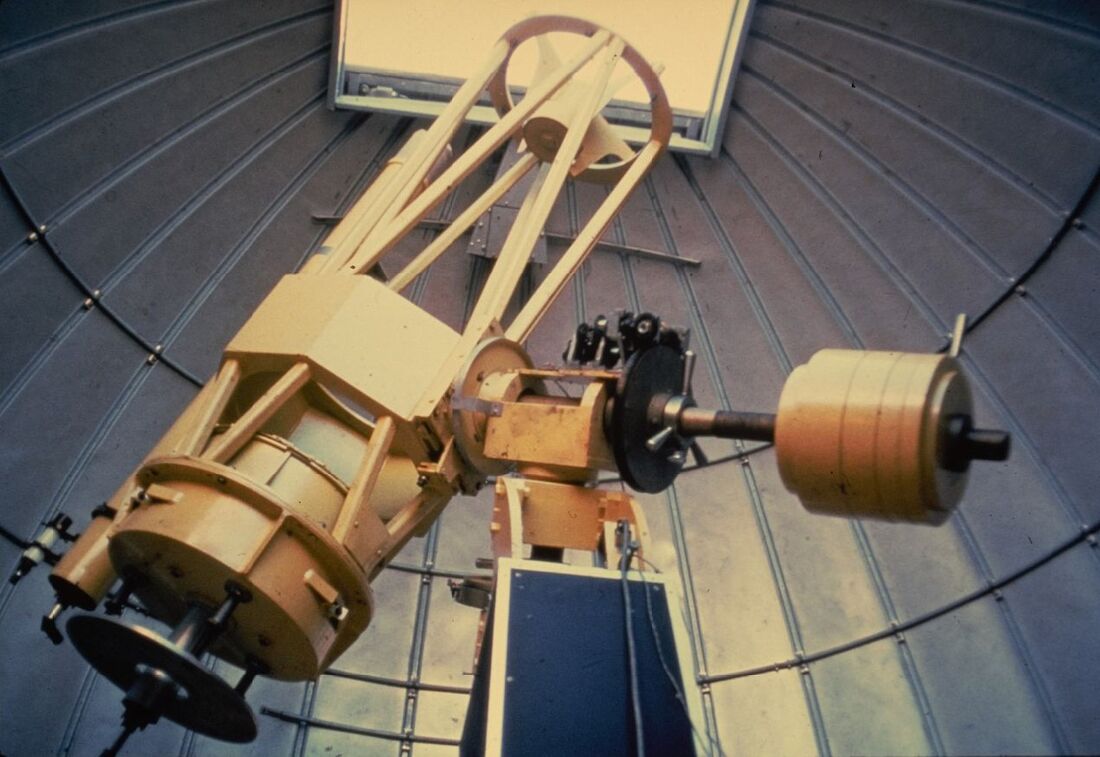

The Goldendale Observatory resulted largely from the efforts of four amateur astronomers based at Clark College in Vancouver, Washington: Don Conner, Mack McConnell, John Marshall, and Omer VanderVelden, who started in 1964 to construct what would become the largest and most sophisticated amateur-built telescope of its day. It was originally intended to replace a 12.5 inch Dall-Kirkham telescope they had previously made for the College in 1963. That instrument got Clark College interested in a much larger telescope, and the College purchased the 24.5 inch (62 cm) diameter 5 inch (13 cm) thick 205 pound (93 Kg) Pyrex disc to make the primary mirror for $800 (~ $7,700 today.)

Don Conner, the most involved amateur astronomer of the four, was a high school dropout, and had apparently been somewhat of a problem child. If this inauspicious beginning was not enough, Don, a retired auto parts worker, had multiple sclerosis severe enough to require use of a wheel chair for most of the project's existence. Don had a driving interest in astronomy and making telescopes. He started out during the depression grinding mirrors from glass furniture coasters and emery dust discarded as waste from the Fuller Glass Company. He studied all the material on astronomy he could obtain. Don became increasingly skilled at telescope mirror making and enjoyed passing on his skills to young people interested in astronomy and amateur telescope making.

Working closely with Don on the grinding, polishing, and constant testing of the observatory's 24½ inch, 205-pound Pyrex mirror was Don's long term Vancouver astronomy club buddy, Mack McConnell. Mack was a glass engraver until an allergy forced him to take a job with the Vancouver Water Department. Another member of the foursome, Omer VanVelden, who usually went by "Van", was an employee of Weber Machine Company. Van worked nights and weekends manufacturing all the intricate gears, shafts, and fittings needed for the new large telescope.

Less involved in mirror making, John Marshall's role was nonetheless crucial. Marshall, a former electrician, did the work on the wiring, switches, motors, and other electrical components. One day John told Don, "I think I can talk the college into financing a large mirror blank. What do you say to a twenty-four and one-half inch?" Perhaps that was the moment the telescope was born. Putting words into action, John had the 205-pound, five-inch thick Pyrex disk on order before the other three members of the group knew what happened.

Some of the materials used to build the telescope were scrap or surplus, and most of it was donated. Clark students built the telescope pier in the college shop. Van made the mounting at various commercial shops during off hours, Marshall and several friends built the electrical controls, and McConnell and Conner, both amateur telescope makers (ATM's), ground and polished the optics. The f/4.9 primary mirror was ground and figured in the Clark College boiler room, where the stable temperature helped ensure a good optical figure for the mirror. The four convex Cassegrain secondary mirrors were finished in Conner's garage, and interference tested with matching concave test mirrors. The telescope was designed to be able to be converted to a Newtonian if and when it was decided to procure a suitable flat secondary mirror and support structure, and a suitable focusing assembly. Together they volunteered nearly six years in building the telescope, and Clark College contributed over $3,000 for materials (~ $25,000 today).

At the time of its completion in 1970, the telescope was valued at $50,000 (~ $350,000 today). However, due to having a night sky being "too light polluted" by nearby Portland and Vancouver, it was decided the telescope could not be used to its full potential if it was sited on the college campus. Clark College sought a better location for the instrument relatively close to the Portland-Vancouver metropolitan area. At first they considered Larch Mountain near Camas, Washington, but decided it was still too close to the light pollution coming from Portland and Vancouver. Locations just to the east of the Cascade Mountains with better weather conditions and much darker night skies then became prime contenders, with travel routes along the Columbia River providing good highway access.

Marshall led the effort to site the telescope; his first choice was to approach Central Washington State College in Ellensburg, Washington, which was ideally placed nearly equidistant from Seattle, Spokane, and Portland/Vancouver. Nearby Table Mountain was a superb location for the telescope, and would become the future location of the Table Mountain Star Party. But the college ultimately decided they were not interested due to the costs involved. Dejected, Marshall, his wife, and Conner headed home. About halfway home they became hungry and the trio stopped at a cafe in the small town of Goldendale for lunch. Striking up a conversation with owner John Toll, Marshall was soon put in touch with Mayor George Nesbitt. A follow-up meeting was arranged and on May 28, 1964, Marshall, McConnell, and VanVelden met with Mayor Nesbitt, Toll, Pete May, editor of the Goldendale Sentinel, and others. The amateur astronomer's proposal included building the observatory for housing the telescope and other instruments, with an astronomy lab, a library, and whatever else was needed.

Soon it was agreed that Clark College would supply the telescope if the City would supply the site and observatory building. Even though Goldendale was relatively small, there were substantial concerns about "too much light emitting from the town's lights" affecting the telescope. The Goldendale City leaders promised to build an observatory for the instrument, and per professional astronomers that were consulted, promised to enact lighting regulations to protect it from light pollution and educate the public of the need to protect it. The non-profit Goldendale Observatory Corporation was formed on April 13, 1971 to solicit funds to build the observatory. The Corporation was led by a volunteer board of directors, which included the telescope makers and Clark College representatives.

The Corporation, Clark College, and the telescope makers stipulated the Observatory's primary mission would be for science education and use by local schools, regional college student learning and lab purposes, the public, and advanced amateur astronomers for their own observing projects. Though not the primary purpose, astronomical research was included, which included photometry and dark-sky object photography of stars and nebulae. Goldendale initially leased 20 acres, and eventually 5 acres of land was donated on which the Observatory was built.

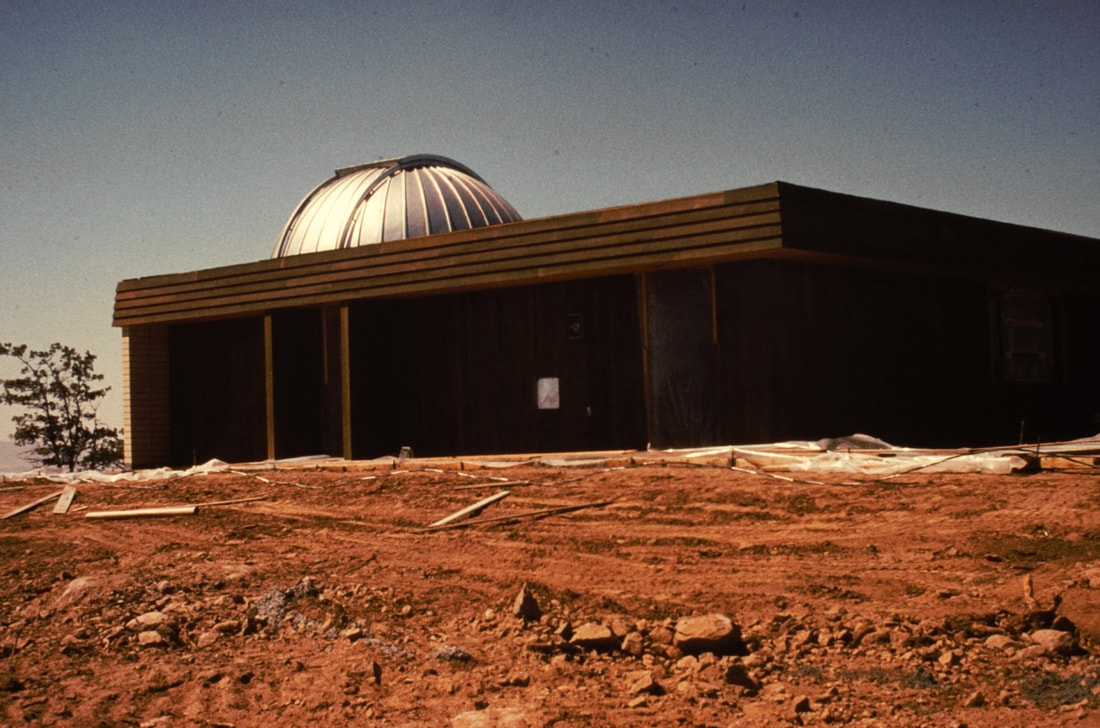

Funds for the building (80%) came via a federal grant of $150,000 (about one million dollars today), and a smaller $25,000 Klickitat Valley Bank loan and donations were to be paid for the 20% matching funds. Clark College then donated the 24½ inch reflecting telescope to the City of Goldendale -- the designated recipient for the federal funds. The Observatory design was based largely on the University of Washington's Manastash Ridge Observatory built west of Ellensburg, Washington, in 1972. In February 1973 construction bids to build the Observatory ranged from $138,000 to $167,000 (~ $970,000 to $1,170,000 today). Tom Hargiss, a Yakima architect, was hired and construction bids were sought. A contract was awarded to Cree Construction Company of Everett, for $138,000.

The Goldendale Observatory was built over a period of four months and finished in September 1973, and an October 13 dedication date was set. Meanwhile, back in Vancouver, the completed 24½ inch mirror was dispatched to get its reflective coating of aluminum. October rolled around and the mirror was not back. An eleventh-hour phone call from Bud Hakanson, President of Clark College, to the mirror coaters got the mirror back to the college on October 9, where it was then taken to the Observatory by private car.

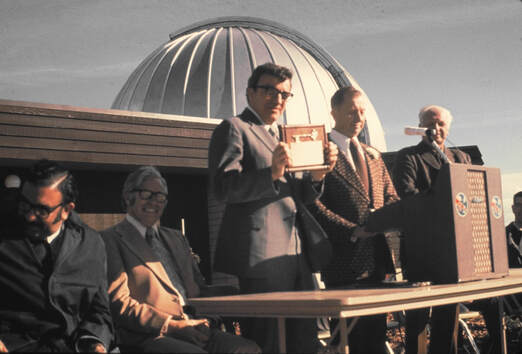

The formal Observatory dedication was held October 13, 1973 attended by over 300 people. In the keynote address, Congressman Mike McCormick, one of the few scientists in Congress, predicted its "success in education and research," and dedicated Goldendale Observatory "to the telescope builders, the people who worked to make the observatory a reality, to the scientists who came before it, and those who will 'seek the truth' as a result of it." The distinguished crowd, including observatory directors and members, mayors, city and county counselors, college presidents, professional and amateur astronomers from all over the northwest, and other guests, rose in a standing ovation as Don Conner struggled up from his wheelchair. With Don's hands trembling, and with Mac, John, and Van at his side, Don was helped to the eyepiece of the telescope for his first look into space from the new Goldendale Observatory.

But the City of Goldendale failed to account for how the Observatory would be operated once they had it. The Observatory Corporation leased the Observatory from the City and agreed to provide for its operation. As the saying goes, they and the City of Goldendale didn't plan to fail, they failed to plan. Every available dime had been poured into the its construction. Unfortunately the Observatory closed immediately after opening, as no funds were left for its maintenance, staffing, needed improvements, or for programming, not to mention how they would repay the 20% bank loan.

For the next two and a half years occasional public use was supported by a small group of amateur astronomers in Goldendale along with many others from Seattle and Portland-Vancouver, with the Observatory generally open one night a week every other week. Central Washington State College offered astronomy classes at the Observatory in 1975 and 1976. The Observatory was entirely dependent on membership dues, user fees, and donations.

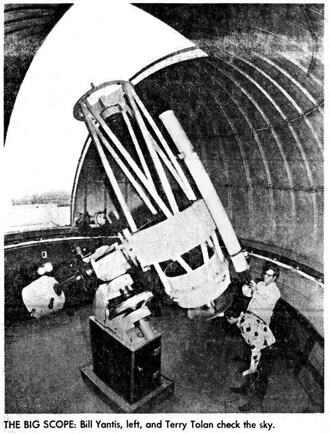

However, these were not sufficient to meet maintenance needs, much less to meet bank payments, pay staff, or make needed equipment purchases and improvements. While Goldendale had steadfastly refused to lend any financial support for the Observatory, faced with potential closure and foreclosure, in April 1976 the Observatory Corporation persuaded the city to help out by providing 2/3 of a $12,000 annual budget (~ $65,000 today). This allowed purchasing much needed telescope equipment such as eyepieces and cameras, and hiring full-time director Mike Uhtoff, who left in September that same year to become director of the Portland Audubon Society. William Yantis took over that October, and had degrees in astronomy and physics from the University of Washington. He was assisted by fellow amateur astronomer Terry Tolan, a Portland State University graduate in Geology.

The Observatory emphasized the use of the facility by the public, schools, and amateur astronomers. It included a kitchen facility for overnight stays, and had a darkroom for processing photographs taken with the instrument. The Observatory offered presentations by amateur astronomers and experts in science and astronomy, showings of science films, as well as hosting astronomy guest speakers, science workshops, and classes in telescope making and astrophotography. By 1978 the Observatory remained so badly in arrears that the Klickitat Valley Bank was forced to write the co-signers of the initial loan, threatening foreclosure. This time rescue came not from earthly sources, but from an event from the sky that was to turn Goldendale into a boomtown for one brief history-making day. It was unthinkable that the Goldendale Observatory could be closed prior to this event, which was to draw 17,000 people to the Goldendale area from around the globe.

The Goldendale Observatory became famous with the February 26, 1979 total solar eclipse, as thousands of visitors and the news media descended on the town of Goldendale for the event. NBC-TV donated $500 (about $1900 today) to the Observatory for the privilege of providing live television broadcasts of the eclipse to the nation and world from the Observatory. The Astronomical League held their annual gathering of amateur astronomers in Goldendale specifically for the eclipse, and generously shared their telescopes with the public. The large amount of attention for the Observatory accompanying the 1979 eclipse put renewed pressure on the City of Goldendale and surrounding Klickitat County to finally adopt the lighting codes which were promised years earlier to protect the night sky for the 24½ inch telescope.

After the eclipse, the Corporation continued to experience insurmountable financial difficulties in paying the bank loans and staffing the Observatory. The city, faced with the need for tough budget cuts, began proposing permanent closure of the Observatory. Discussions then began about purchase of the Observatory by the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission. In April 1979 the State Legislature agreed to purchase the site for the far below-cost bargain basement price of $100,000 (~ $340,000 today), which paid off the Corporation creditors, and would "bail out" Goldendale by providing an additional $80,000 for two years of interim funding to operate it through 1981, and fund paving the "cow path" dirt road leading up to the Observatory.

Not long after this Yantis left in mid 1979. The Observatory Corporation hired Gary Fouts, who had a degree in Astronomy from San Diego State University and teaching credentials at the community college level. Fouts continued to work with the state for funding which began under Yantis. This included Governor Dixie Lee Ray (a fellow scientist) to solidify long-term funding for staffing and operations after the actual transfer of operations to Washington State Parks two years later. However, Fouts was also concerned "that some Goldendale Observatory programs will be inhibited or phased out in the future." While Fouts made several important contributions to the Goldendale Observatory operations, he also realized the precarious funding situation at the Observatory would remain even after the State's purchase, and he additionally didn't want to become a law-enforcement oriented State Park Ranger. He left in March 1981 to do research at Mount Wilson Observatory in southern California.

By March of 1981 the Observatory Corporation Board had hired Steve Stout, an electronic technician who had done quality assurance work for a large computer service, and who was an amateur astronomer with the Seattle Astronomical Society. Stout also participated in a community concert band and a mountaineering club. Stout earned his degree in physics from Pacific Lutheran University in 1969, and like Fouts before him, was paid by Washington State Parks via the Observatory Corporation for interim funding for staffing and operations. The Parks Commission assumed full operation on July 1, 1981. Rather than becoming a Park Ranger, Stout became the first "Interpretive Specialist" in the Washington State Parks system. Stout said the Goldendale Observatory position was a dream come true, where he "could put in heavy hours here and still go home relaxed."

The Goldendale Observatory Corporation transitioned to become the Friends of Goldendale Observatory, which helped to support the mission to further public science and astronomy education. For almost four decades, the Goldendale Observatory State Park has provided public education and views of the heavens with a full-time Interpretive Specialist, part-time Park Aids, as well as volunteers. The Goldendale Observatory was named as an official Washington State Park Heritage Site in 2014.

While Stout struggled as those before with ongoing funding and support issues, in 2010 - thanks to his efforts and with the help of other amateur astronomers - the Goldendale Observatory once again gained worldwide recognition by being awarded one of the first International Dark Sky Park designations by the International Dark-Sky Association. This designation fit perfectly with the original promises made by City of Goldendale and Klickitat County officials (and their subsequently adopted regulations), to protect the telescope's view of the night sky from light pollution from nearby Goldendale, and their pledges to educate the public about the importance of protecting the night sky for the Observatory.

However, this designation was short-lived. In 2017 - three years after Stout retired - the IDA revoked the Goldendale Observatory State Parks designation as an International Dark Sky Park due to the failure of Washington State Parks Area Manager Lem Pratt and Interpretive Specialist Troy Carpenter to meet the responsibilities of providing education about the importance of a dark night sky for the Park and promote its conservation. Washington State Parks stated education about light pollution and the previously adopted lighting codes to protect it were now a "hot button issue" for the City of Goldendale and Klickitat County. The IDA also noted the apparent lack of support by Goldendale and Klickitat County for conservation of the Goldendale Observatory State Park's night sky, and rightly stated that without the leadership and support of Washington State Parks, the Park's night sky would suffer degradation via light pollution coming from adjacent Goldendale and surrounding Klickitat County.

Following the International Dark Sky Park revocation, Washington State Parks stated in 2019 they would work with the local community to have the status reinstated. This effort apparently failed for unknown reasons. Despite having stated preserving the dark night sky "cherished natural heritage" for the Observatory was part of its "mission," and that it would provide "educational opportunities" in support of night sky conservation; in 2021 Washington State Parks announced the International Dark Sky Park designation was "not a good fit for Washington State Parks operating policy," "not a part of its mission," and furthermore an International Dark Sky Park designation was something they would "go out of their way to avoid." Washington State Parks now explicitly states "tourism is our primary focus" for the Goldendale Observatory State Park, and the local Goldendale Chamber of Commerce referred to it as an "amusement park" for "filling up hotel and restaurant spaces."

In spite of being a Washington State Park Heritage Site, apparently the original intent and need for a dark night sky for the Observatory's historic telescope is no longer considered part of the Observatory's "heritage" by Washington State Parks or the local community, and deserving of meaningful advocacy for conservation or protection. This cemented the fact that the Goldendale Observatory State Park would remain the first - and so far the only - International Dark Sky Place to ever be decertified in the world.

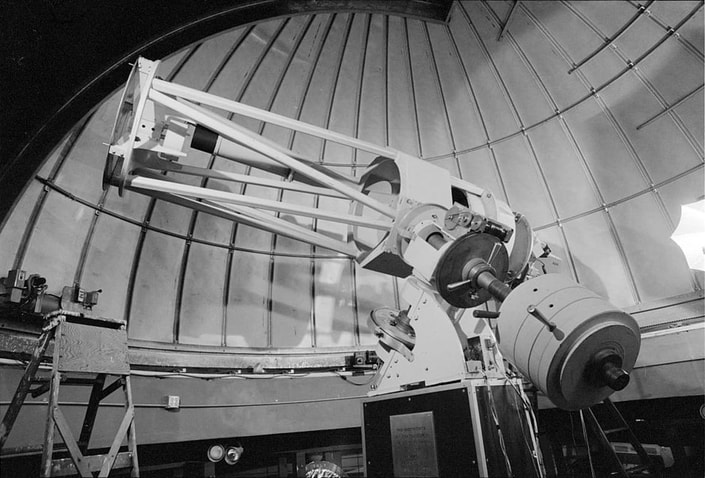

From 2015 to 2019, the Observatory received telescope upgrades and a major renovation and expansion with public costs totaling almost $6 million. While the historic 24½ inch telescope and its dome structure remained largely intact but hidden behind a new facade, the rest of the facility was demolished to make way for a larger and more modern building with improved infrastructure, more seating and interpretive displays, new landscaping, and enlarged parking capacity.

Don Conner, the most involved amateur astronomer of the four, was a high school dropout, and had apparently been somewhat of a problem child. If this inauspicious beginning was not enough, Don, a retired auto parts worker, had multiple sclerosis severe enough to require use of a wheel chair for most of the project's existence. Don had a driving interest in astronomy and making telescopes. He started out during the depression grinding mirrors from glass furniture coasters and emery dust discarded as waste from the Fuller Glass Company. He studied all the material on astronomy he could obtain. Don became increasingly skilled at telescope mirror making and enjoyed passing on his skills to young people interested in astronomy and amateur telescope making.

Working closely with Don on the grinding, polishing, and constant testing of the observatory's 24½ inch, 205-pound Pyrex mirror was Don's long term Vancouver astronomy club buddy, Mack McConnell. Mack was a glass engraver until an allergy forced him to take a job with the Vancouver Water Department. Another member of the foursome, Omer VanVelden, who usually went by "Van", was an employee of Weber Machine Company. Van worked nights and weekends manufacturing all the intricate gears, shafts, and fittings needed for the new large telescope.

Less involved in mirror making, John Marshall's role was nonetheless crucial. Marshall, a former electrician, did the work on the wiring, switches, motors, and other electrical components. One day John told Don, "I think I can talk the college into financing a large mirror blank. What do you say to a twenty-four and one-half inch?" Perhaps that was the moment the telescope was born. Putting words into action, John had the 205-pound, five-inch thick Pyrex disk on order before the other three members of the group knew what happened.

Some of the materials used to build the telescope were scrap or surplus, and most of it was donated. Clark students built the telescope pier in the college shop. Van made the mounting at various commercial shops during off hours, Marshall and several friends built the electrical controls, and McConnell and Conner, both amateur telescope makers (ATM's), ground and polished the optics. The f/4.9 primary mirror was ground and figured in the Clark College boiler room, where the stable temperature helped ensure a good optical figure for the mirror. The four convex Cassegrain secondary mirrors were finished in Conner's garage, and interference tested with matching concave test mirrors. The telescope was designed to be able to be converted to a Newtonian if and when it was decided to procure a suitable flat secondary mirror and support structure, and a suitable focusing assembly. Together they volunteered nearly six years in building the telescope, and Clark College contributed over $3,000 for materials (~ $25,000 today).

At the time of its completion in 1970, the telescope was valued at $50,000 (~ $350,000 today). However, due to having a night sky being "too light polluted" by nearby Portland and Vancouver, it was decided the telescope could not be used to its full potential if it was sited on the college campus. Clark College sought a better location for the instrument relatively close to the Portland-Vancouver metropolitan area. At first they considered Larch Mountain near Camas, Washington, but decided it was still too close to the light pollution coming from Portland and Vancouver. Locations just to the east of the Cascade Mountains with better weather conditions and much darker night skies then became prime contenders, with travel routes along the Columbia River providing good highway access.

Marshall led the effort to site the telescope; his first choice was to approach Central Washington State College in Ellensburg, Washington, which was ideally placed nearly equidistant from Seattle, Spokane, and Portland/Vancouver. Nearby Table Mountain was a superb location for the telescope, and would become the future location of the Table Mountain Star Party. But the college ultimately decided they were not interested due to the costs involved. Dejected, Marshall, his wife, and Conner headed home. About halfway home they became hungry and the trio stopped at a cafe in the small town of Goldendale for lunch. Striking up a conversation with owner John Toll, Marshall was soon put in touch with Mayor George Nesbitt. A follow-up meeting was arranged and on May 28, 1964, Marshall, McConnell, and VanVelden met with Mayor Nesbitt, Toll, Pete May, editor of the Goldendale Sentinel, and others. The amateur astronomer's proposal included building the observatory for housing the telescope and other instruments, with an astronomy lab, a library, and whatever else was needed.

Soon it was agreed that Clark College would supply the telescope if the City would supply the site and observatory building. Even though Goldendale was relatively small, there were substantial concerns about "too much light emitting from the town's lights" affecting the telescope. The Goldendale City leaders promised to build an observatory for the instrument, and per professional astronomers that were consulted, promised to enact lighting regulations to protect it from light pollution and educate the public of the need to protect it. The non-profit Goldendale Observatory Corporation was formed on April 13, 1971 to solicit funds to build the observatory. The Corporation was led by a volunteer board of directors, which included the telescope makers and Clark College representatives.

The Corporation, Clark College, and the telescope makers stipulated the Observatory's primary mission would be for science education and use by local schools, regional college student learning and lab purposes, the public, and advanced amateur astronomers for their own observing projects. Though not the primary purpose, astronomical research was included, which included photometry and dark-sky object photography of stars and nebulae. Goldendale initially leased 20 acres, and eventually 5 acres of land was donated on which the Observatory was built.

Funds for the building (80%) came via a federal grant of $150,000 (about one million dollars today), and a smaller $25,000 Klickitat Valley Bank loan and donations were to be paid for the 20% matching funds. Clark College then donated the 24½ inch reflecting telescope to the City of Goldendale -- the designated recipient for the federal funds. The Observatory design was based largely on the University of Washington's Manastash Ridge Observatory built west of Ellensburg, Washington, in 1972. In February 1973 construction bids to build the Observatory ranged from $138,000 to $167,000 (~ $970,000 to $1,170,000 today). Tom Hargiss, a Yakima architect, was hired and construction bids were sought. A contract was awarded to Cree Construction Company of Everett, for $138,000.

The Goldendale Observatory was built over a period of four months and finished in September 1973, and an October 13 dedication date was set. Meanwhile, back in Vancouver, the completed 24½ inch mirror was dispatched to get its reflective coating of aluminum. October rolled around and the mirror was not back. An eleventh-hour phone call from Bud Hakanson, President of Clark College, to the mirror coaters got the mirror back to the college on October 9, where it was then taken to the Observatory by private car.

The formal Observatory dedication was held October 13, 1973 attended by over 300 people. In the keynote address, Congressman Mike McCormick, one of the few scientists in Congress, predicted its "success in education and research," and dedicated Goldendale Observatory "to the telescope builders, the people who worked to make the observatory a reality, to the scientists who came before it, and those who will 'seek the truth' as a result of it." The distinguished crowd, including observatory directors and members, mayors, city and county counselors, college presidents, professional and amateur astronomers from all over the northwest, and other guests, rose in a standing ovation as Don Conner struggled up from his wheelchair. With Don's hands trembling, and with Mac, John, and Van at his side, Don was helped to the eyepiece of the telescope for his first look into space from the new Goldendale Observatory.

But the City of Goldendale failed to account for how the Observatory would be operated once they had it. The Observatory Corporation leased the Observatory from the City and agreed to provide for its operation. As the saying goes, they and the City of Goldendale didn't plan to fail, they failed to plan. Every available dime had been poured into the its construction. Unfortunately the Observatory closed immediately after opening, as no funds were left for its maintenance, staffing, needed improvements, or for programming, not to mention how they would repay the 20% bank loan.

For the next two and a half years occasional public use was supported by a small group of amateur astronomers in Goldendale along with many others from Seattle and Portland-Vancouver, with the Observatory generally open one night a week every other week. Central Washington State College offered astronomy classes at the Observatory in 1975 and 1976. The Observatory was entirely dependent on membership dues, user fees, and donations.

However, these were not sufficient to meet maintenance needs, much less to meet bank payments, pay staff, or make needed equipment purchases and improvements. While Goldendale had steadfastly refused to lend any financial support for the Observatory, faced with potential closure and foreclosure, in April 1976 the Observatory Corporation persuaded the city to help out by providing 2/3 of a $12,000 annual budget (~ $65,000 today). This allowed purchasing much needed telescope equipment such as eyepieces and cameras, and hiring full-time director Mike Uhtoff, who left in September that same year to become director of the Portland Audubon Society. William Yantis took over that October, and had degrees in astronomy and physics from the University of Washington. He was assisted by fellow amateur astronomer Terry Tolan, a Portland State University graduate in Geology.

The Observatory emphasized the use of the facility by the public, schools, and amateur astronomers. It included a kitchen facility for overnight stays, and had a darkroom for processing photographs taken with the instrument. The Observatory offered presentations by amateur astronomers and experts in science and astronomy, showings of science films, as well as hosting astronomy guest speakers, science workshops, and classes in telescope making and astrophotography. By 1978 the Observatory remained so badly in arrears that the Klickitat Valley Bank was forced to write the co-signers of the initial loan, threatening foreclosure. This time rescue came not from earthly sources, but from an event from the sky that was to turn Goldendale into a boomtown for one brief history-making day. It was unthinkable that the Goldendale Observatory could be closed prior to this event, which was to draw 17,000 people to the Goldendale area from around the globe.

The Goldendale Observatory became famous with the February 26, 1979 total solar eclipse, as thousands of visitors and the news media descended on the town of Goldendale for the event. NBC-TV donated $500 (about $1900 today) to the Observatory for the privilege of providing live television broadcasts of the eclipse to the nation and world from the Observatory. The Astronomical League held their annual gathering of amateur astronomers in Goldendale specifically for the eclipse, and generously shared their telescopes with the public. The large amount of attention for the Observatory accompanying the 1979 eclipse put renewed pressure on the City of Goldendale and surrounding Klickitat County to finally adopt the lighting codes which were promised years earlier to protect the night sky for the 24½ inch telescope.

After the eclipse, the Corporation continued to experience insurmountable financial difficulties in paying the bank loans and staffing the Observatory. The city, faced with the need for tough budget cuts, began proposing permanent closure of the Observatory. Discussions then began about purchase of the Observatory by the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission. In April 1979 the State Legislature agreed to purchase the site for the far below-cost bargain basement price of $100,000 (~ $340,000 today), which paid off the Corporation creditors, and would "bail out" Goldendale by providing an additional $80,000 for two years of interim funding to operate it through 1981, and fund paving the "cow path" dirt road leading up to the Observatory.

Not long after this Yantis left in mid 1979. The Observatory Corporation hired Gary Fouts, who had a degree in Astronomy from San Diego State University and teaching credentials at the community college level. Fouts continued to work with the state for funding which began under Yantis. This included Governor Dixie Lee Ray (a fellow scientist) to solidify long-term funding for staffing and operations after the actual transfer of operations to Washington State Parks two years later. However, Fouts was also concerned "that some Goldendale Observatory programs will be inhibited or phased out in the future." While Fouts made several important contributions to the Goldendale Observatory operations, he also realized the precarious funding situation at the Observatory would remain even after the State's purchase, and he additionally didn't want to become a law-enforcement oriented State Park Ranger. He left in March 1981 to do research at Mount Wilson Observatory in southern California.

By March of 1981 the Observatory Corporation Board had hired Steve Stout, an electronic technician who had done quality assurance work for a large computer service, and who was an amateur astronomer with the Seattle Astronomical Society. Stout also participated in a community concert band and a mountaineering club. Stout earned his degree in physics from Pacific Lutheran University in 1969, and like Fouts before him, was paid by Washington State Parks via the Observatory Corporation for interim funding for staffing and operations. The Parks Commission assumed full operation on July 1, 1981. Rather than becoming a Park Ranger, Stout became the first "Interpretive Specialist" in the Washington State Parks system. Stout said the Goldendale Observatory position was a dream come true, where he "could put in heavy hours here and still go home relaxed."

The Goldendale Observatory Corporation transitioned to become the Friends of Goldendale Observatory, which helped to support the mission to further public science and astronomy education. For almost four decades, the Goldendale Observatory State Park has provided public education and views of the heavens with a full-time Interpretive Specialist, part-time Park Aids, as well as volunteers. The Goldendale Observatory was named as an official Washington State Park Heritage Site in 2014.

While Stout struggled as those before with ongoing funding and support issues, in 2010 - thanks to his efforts and with the help of other amateur astronomers - the Goldendale Observatory once again gained worldwide recognition by being awarded one of the first International Dark Sky Park designations by the International Dark-Sky Association. This designation fit perfectly with the original promises made by City of Goldendale and Klickitat County officials (and their subsequently adopted regulations), to protect the telescope's view of the night sky from light pollution from nearby Goldendale, and their pledges to educate the public about the importance of protecting the night sky for the Observatory.

However, this designation was short-lived. In 2017 - three years after Stout retired - the IDA revoked the Goldendale Observatory State Parks designation as an International Dark Sky Park due to the failure of Washington State Parks Area Manager Lem Pratt and Interpretive Specialist Troy Carpenter to meet the responsibilities of providing education about the importance of a dark night sky for the Park and promote its conservation. Washington State Parks stated education about light pollution and the previously adopted lighting codes to protect it were now a "hot button issue" for the City of Goldendale and Klickitat County. The IDA also noted the apparent lack of support by Goldendale and Klickitat County for conservation of the Goldendale Observatory State Park's night sky, and rightly stated that without the leadership and support of Washington State Parks, the Park's night sky would suffer degradation via light pollution coming from adjacent Goldendale and surrounding Klickitat County.

Following the International Dark Sky Park revocation, Washington State Parks stated in 2019 they would work with the local community to have the status reinstated. This effort apparently failed for unknown reasons. Despite having stated preserving the dark night sky "cherished natural heritage" for the Observatory was part of its "mission," and that it would provide "educational opportunities" in support of night sky conservation; in 2021 Washington State Parks announced the International Dark Sky Park designation was "not a good fit for Washington State Parks operating policy," "not a part of its mission," and furthermore an International Dark Sky Park designation was something they would "go out of their way to avoid." Washington State Parks now explicitly states "tourism is our primary focus" for the Goldendale Observatory State Park, and the local Goldendale Chamber of Commerce referred to it as an "amusement park" for "filling up hotel and restaurant spaces."

In spite of being a Washington State Park Heritage Site, apparently the original intent and need for a dark night sky for the Observatory's historic telescope is no longer considered part of the Observatory's "heritage" by Washington State Parks or the local community, and deserving of meaningful advocacy for conservation or protection. This cemented the fact that the Goldendale Observatory State Park would remain the first - and so far the only - International Dark Sky Place to ever be decertified in the world.

From 2015 to 2019, the Observatory received telescope upgrades and a major renovation and expansion with public costs totaling almost $6 million. While the historic 24½ inch telescope and its dome structure remained largely intact but hidden behind a new facade, the rest of the facility was demolished to make way for a larger and more modern building with improved infrastructure, more seating and interpretive displays, new landscaping, and enlarged parking capacity.

Thousands of people traveled to Goldendale to see the 1979 total solar eclipse, which made the Goldendale Observatory famous. Amateur Astronomers attending the Astronomical League's Annual Meeting and hosted by the Observatory generously shared their telescopes with the public to view the partial phases of the eclipse.

|

Third Goldendale Observatory Director Gary Fouts saw the completion of the transfer of operation of the Observatory to Washington State Parks. After leaving the Observatory he went on to become a full-time professional astronomer and educator, and worked on the Hubble Space Telescope team.

|

For over 30 years, Washington State Parks Interpretive Specialist Steve Stout emphasized the importance of conservation of the Goldendale Observatory night sky. Stout, along with Washington amateur astronomers, brought world-wide recognition to the Observatory with a highly coveted International Dark Sky Park certification in 2010.

|

After Stout retired, the Goldendale Observatory lost the prestigious International Dark Sky Park designation in 2017 due to new Washington State Park management and Observatory staff who decided they would not fulfill the requirements Washington State Parks had originally agreed to: Provide dark night sky education programs and promote conservation of the International Dark Sky Park's night sky.

Washington State Parks Ranger and Area Manager Lem Pratt called the International Dark Sky Park "part of an environmentalist agenda" he wanted to "go away," and Interpretive Specialist Troy Carpenter referred to night sky conservation education as "unpopular" "hippy-dippy activism," and "pandering to amateur astronomers," who he claims "devolve observatories in to clubhouses." Together they were responsible for the first ever Dark Sky Place revocation in the history of the Dark Sly Places program of the International Dark-Sky Association.

|

Evolution of renovation design, demolition, 24½ inch telescope dome enclosure takes shape.

Observatory nearing completion - August 2019:

A panoramic flyover and photography by J.B. Nokes Photography. Music: Ketsa "Seeing You Again."

The Completed Observatory Spring 2020